Wе already know that most of the issues we encounter when dealing with color are connected with human perception (both the viewer’s and the photographer’s), and with the fact that software developers and hardware producers tend to forego thinking about color aesthetics. Having enough visual experience, you can achieve color harmony even with the most imperfect software. Moreover, you can minimize your “software exposure” by shooting with film or straight to JPEG. On the other hand, even superior tools are of little help if you don’t have a necessary visual background.

Any digital photo processor can be used to produce both great and bleak images. The tools we are using can either assist or hinder us on the chosen path. But the path is our choice, determined by the photographic vision, artistic taste and sense of where we are going – not by the tools we use. Thus, your tool skills play less of a role in determining the quality of the resulting image, because the decisions are ultimately the photographer’s choice, and they are driven by individual taste, whether you are using the tools intuitively or applying presets developed by somebody else.

That is why I think a lot of people will find this book useful regardless of the software you are using. Who knows, maybe I will even inspire some of my readers to embark on their own experiments. For me, it is important to share what I have learned, over many years spent studying and researching, with those of you who wish to move further in achieving greater color expression.

Having tried a lot of raw converters and photo processing tools, having studied the possibilities of raw conversion, I finally found the solution that was a perfect fit on all counts, from the process to the result. I have already mentioned the name of the program, it’s a lesser known raw converter, RPP (Raw Photo Processor), developed by two Soviet-born American photographers. Having first developed RPP for personal use, they are now sharing it with the world.

I’ll be honest with you: my first experience with RPP was short and uninspiring. The program’s interface looked counterintuitive, I couldn’t do any work in it, and my efforts, predictably, yielded no result. I forgot all about the program and only came back to it after a year or so of looking for a more intuitive tool that would feel “just right”. At that point, I never considered RPP as a likely candidate for the role: again, I didn’t understand the logic of this program and I couldn’t evaluate its usefulness. However, a lot of my colleagues who had been following my experiments persistently nudged me in the direction of RPP. I didn’t like the idea at all and pretty much ignored their advice, until, having literally run out of options to choose from, I finally caved in and launched the software for the second time, a year after I had first downloaded it.

During that year, however, my perception must have somehow shifted. Now, the interface started making a lot of sense – it looked much more logical than the typical solutions other developers had been offering. The result of raw conversion (done in under a minute) was simply stunning. I fell in love… at second sight.

Later, when I learned more about this program, I found out that it had not been developed by programmers. The people behind RPP are photographers, with one of them having more than forty years of experience, including training at Kodak, where all major studies of color perception in photography originate. What is more, the development of the program is an ongoing collaboration with like-minded professionals from around the world. Thus, the experts evaluating this software and its functionality are people who understand aesthetics better than computer programming.

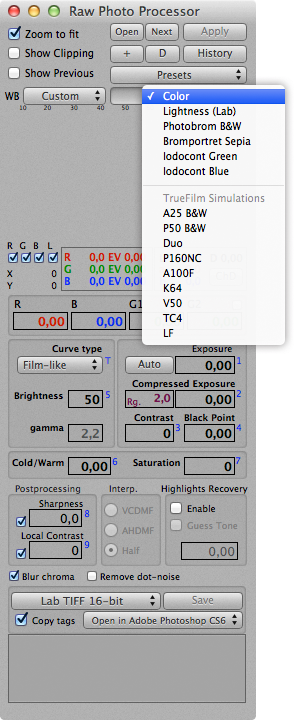

As it turned out, the program’s unusual interface (fig. 19.1) was designed to reflect the photographic logic. The developers themselves call their product “a digital developer solution” where you “dunk” your raw files. Compared to other raw converters, RPP has quite a few advantages that I will detail below.

Figure 19.1

RPP Advantages

1. Raw-conversion and luminosity algorithms rely on Film-like contrast curves.

We already know from the previous chapters that raw files are often low-contrast and dark. Thus, sometimes the original luminosity levels need redistribution, or contrast needs a boost.

Most converters and photo processing software solutions go about these transformations by applying a curve (or several curves) of a particular shape. Even changing values with sliders like Brightness and Contrast is actually translated into a curve that is then applied to the image, although the user doesn’t see the curve itself. Moreover, there is often an option to create your own curve, which can be applied as an additional post-processing step.

RPP, too, changes raw data to alter contrast values. However, these transformations are integrated into the process of conversion itself and are therefore not carried out post factum. For our purposes, we will still use the term “contrast curve” to describe these changes, although now we know that RPP applies this curve earlier than most other software solutions. In RPP, each value setting (Brightness, Contrast, Black Point, Exposure, etc.) influences a designated part of the contrast curve, so its final shape is determined by the combination of all settings.

As a starting point, you can select one of the pre-set contrast curve shapes: Film-like, Gamma or L*. The Film-like curve, set as default, is an intricately shaped curve designed to mimic the process of film development; in other words, it is based on the same artistic logic and assumptions as those behind photographic film. A photographer using RPP will thus be able to get an aesthetically pleasing image without having to apply multiple mutually desynchronized curves.

2. Correct white balance.

White balancing in RPP is very straightforward. It is implemented by giving the user direct control over the exposure coefficients for each of the four channels of the RGBG Bayer matrix. Many of you will be used to dealing with Temperature/Tint settings in other converters, so the RPP approach will seem strange and counter-intuitive. Yet, in practice, it offers a more efficient tool for regulating the white balance without having to deal with color shifts. By maintaining a correct white balance, RPP manages to minimize both the “red face” and the “violet shadow” effects that typically occur when one tries to boost contrast in other photo processors.

For example, to make a picture warmer, you normally increase the Temperature value in a raw converter. In RPP, this will translate into a simultaneous increase of R and decrease of B. Yet the system is flexible: you are free to toggle either channel as you please (they don’t have to be strictly parallel), or you can change one, leave out the other, or add the third (G1) and even the fourth one (G2).

In popular converters, fine-tuning white balance is much more difficult: because their internal algorithms are non-linear and overcomplicated, the result is often dubious. In RPP, managing white balance is no longer a thing-in-itself.

3. Photographic contrast with a priority in shadows.

When you increase contrast in RPP, it prioritizes shadows over highlights. In other words, the shadows become more intensive than the highlights, which is exactly what we see in fine art and film photography.

4. Compressed exposure.

Compressed exposure in RPP is a direct descendant of the processes that accompany the development of negatives. When you shoot to negative film, the colors don’t disappear completely, even with overexposure. Shooting to raw file, however, is merciless to color, but if the frame has not been overexposed, you can increase its general compressed exposure just as you would have done with film, i.e. without the loss of detail in the highlights. To achieve this in other converters, you would have to apply selective tools (like Recovery, Whites or Highlights in Adobe Lightroom), which often destroy the image integrity, since recovering selected tonal ranges leaves the others intact and the entire image looks unnaturally unbalanced. In RPP, this is done through a redistribution of lighting and contrast within the entire tonal makeup of the image.

5. Delicate Black point management.

RPP is careful with both highlights and shadows. Increasing the Black point value will make it denser, but not to the point of elimination.

6. Floating-point math is used for calculating values.

Applying floating-point math, rather than integer math, eliminates error accumulation and leads to better quality of colors, superior tonal distribution and higher detailization of colors (both in shades and highlights).

7. Raw-files are converted with minimal changes to the original data.

For example, there is no blurring of the channels of which other converters are sometimes “guilty”. Normally, this is done to get a softer image, but the result is often somewhat damaging to the original. RPP developers trust the user to do the blurring in case the image looks too detailed, and many believe that RPP-converted images are excessively sharp. We know now that this is not an added feature – but, rather, a removed one.

8. Histogram visualization is tied to the Adams Zones scales.

Most of the RPP values, including the Black and White point values, can be set after analysis of the histogram; there is no need to spend too much time trying different values to see if any of them will fit. You can also measure the luminosity of any portion of your image and its correspondence to the Adams Zones, a classical exposure solution for film photographers.

9. Accurate camera profiler.

Color profiles are rigorously set up for each camera, which helps to avoid the color deciphering problems typical of many other converters (specifically, RPP-converted reds don’t suffer from either overburning or loss of detail).

10. Application of any change means a fresh interpolation of raw data.

In other words, RPP demosaics the data anew, each time you introduce alterations. This enables the program to account for all value changes at the earliest stages of raw data interpretation. In other raw converters, each rendering of new settings is, in fact, “refurbishing on top of the original demosaiced data”. In RPP, post-processing is an integral part of raw data conversion.

11. TrueFilm profiles.

Even if RPP didn’t have this option, it would still have its well-deserved place among the new generation of raw converters which give you high quality pictures with brilliant colors in a very short time. With its TrueFilm profiles, however, RPP has delivered a truly revolutionary software solution.

I will talk a lot about TrueFilm in the next chapter, so right now I would like to address those who are thinking of checking out RPP. As I have already mentioned, at first the program seems counterintuitive and not worth bothering about. Almost every first time user gets this impression, and there are several reasons for that:

- Strange interface, which really is dramatically different from your familiar, standard-issue raw converter look.

- No sliders and, instead, fields to add numerical values.

- Unusual White balance management.

- Having to click “Apply” every time you adjust a setting.

- Relatively slow processing speed. After you have clicked “Apply”, it takes RPP five to ten seconds to generate a preview, and up to thirty seconds to construct a full-size version of your image.

People often make these points when they talk about the “disadvantages” of RPP, but I have a different opinion on the topic, hence the inverted commas. RPP implements an entirely different logic of photo processing – that of a photographer, not that of a software developer. Once you figure out how these “disadvantages” work, they turn into your greatest allies. To help you with this, I have written a step-by-step beginner’s guide to RPP; it can be found in Appendix B at the end of this book. You will find a lot of details and explanations there. Right now, however, I want to stick to some more general comments.

It is important to understand that the high-precision math that is required for better color rendition, among other things, will eat up some of your computer’s “horsepower”. This is why RPP users experience the five- to ten-seconds lag – this time is used to re-calculate the entire image, and clicking “Apply” is needed to launch recalculation. Without the “Apply” button, every change of value would automatically trigger a recalculation and freeze up the system, which would make the program virtually impossible to use.

Yet the time you lose to mathematics is compensated by the time you gain through choosing RPP over other processors. With enough experience, you will learn which changes you need to introduce before clicking “Apply”. In the end, each conversion will only require three to four iterations, bringing the total time of raw-processing down to twenty or thirty seconds per image. A lot of users think that you should only bother with RPP when you are about to process your best images, as so much time is taken up by calculations. In reality, you pick up the pace as you go along, and soon learn to process batches of images in RPP. I personally know a few wedding photographers who use RPP to batch-process photos and spend far less time than they would have done by using Lightroom for this purpose. They still use Lightroom for cataloguing, though.

I have to mention that RPP only works with Mac OS. Largely because it is a personal project and the developers are creating this software for their own needs and distributing it for free, it is highly unlikely that the program will be launched on any other platform any time soon. If you are using Microsoft Windows, you can try running RPP through virtualization software, like VirtualBox or VMWare. It may be a little less convenient than installing RPP in its native Mac OS environment, but there are people who have succeeded in using RPP with Windows, and they say the installation process has not been very difficult. You will find a lot of online guidelines on how to use virtualization software.

Personally, I think that RPP is the most efficient raw conversion tool currently in existence, but I am not in the business of advertising and my plans do not include convincing you to immediately drop whatever you have been doing and start using this software. Moreover, for the sake of being objective, I will discuss the differences between RPP and Lightroom photo processing in one of the following chapters. Please, remember, that my goal is to share the experience and knowledge I have accumulated through a lot of creative “shopping around”; but it is you who will decide what tools you will use, what creative tasks you will solve and what criteria you will apply to the final result.

LIFELIKE: A book on color in digital photography